how to reach every corner (1992 – 2013)

by Gaby Hartel

Close your physical eye so that you first see your painting with your spiritual eye. Then bring to light what you saw in the darkness, so that it may act on others, from inside to outside.

Caspar David Friedrich1

When were you last enveloped by complete darkness? The kind of utter darkness that has an almost physical feel to it: odd, uncomfortable; a sensation, almost, of being stuck in a two-dimensional space, pressed up against a wall, while at the same time being weighted down by some kind of heavy mass folding around you like liquid wax. Your nervous system instantly

Switches to a mode of emergency, calling to its aid all the senses, which are normally dominated by the visual. So that after the first moment of shock you stop staring helplessly into the dark and, instead, start feeling out the space surrounding you in a different way. Until, gradually,

your whole physical being seems to expand into the undefined and vast velvety blackness. For the nonclaustrophobic, this unexpected feeling of floating is mostly a pleasant sensation, fit to denounce all negative connotations that our culture reflexively attributes to

all matters black. And as the all-encompassing darkness unbinds you from the physical laws in which you normally function, you start losing your balance in a very productive way, thereby letting you enter the realm of heightened sensibility, perceptivity, and imagination.

seeing with eyes closed (2013)

Miraculously, your vision, too, is restored, if in a different way: you start perceiving little dots of flickering light, flashes of colour and white light or mouches volantes. This all happens in your head, of course. But it mirrors visual sensations, which you have experienced before:

I’m referring to the scratches or specks of dust which used to pop up as erratic small shapes of light in the old cinema days on the otherwise black screen before the film started. “You are now”, these hors d’oeuvre cinemamoments seemed to suggest, “in a space where anything could happen”. A K Dolven welcomes such chance light effects into her work and refers to them as “happy mistakes”, valuing the constructive unbalance that an overexposure to darkness may have on you.

teenagers lifting the sky (2014)

“Seeing with eyes closed”, says an inscription on Dolven’s studio wall. And the round, energetic longhand in which the artist penciled this is one of many tactile

traces she leaves in on the gallery walls too.

In Dolven’s new series of oil paintings of varying formats, she immerses her viewers into a matte, shimmering, multi-layered darkness, specked with the odd dot or flash of light, here and there. She makes use of the tactile capacity of the eye, invoking a strong physical sensation of unbalance, which is at the same time linked to a kind of fingertip memory. By consciously being vague about scope and perspective in her work, Dolven upsets our need for orientation in a given (pictorial) space. The themes in her paintings can be seen both as something immense and something minute, as her (and our) angle of vision seems to be in a constant process of zooming in or zooming out. As in most of her work, the artist’s new paintings investigate the tension, which this interplay of intimacy and immensity acts out on her viewers’ perceptual and emotional apparatus.

what happens when you fall against a wall or a painting (2014)

As any other artist, Dolven likes to see her work process as a dialogue with the material. And the calculated chance-procedure, which she applies in the course of painting, is, indeed, in many ways a communicative act. The artist interacts with her work in performative stages, first creating a material fact (a layer of gesso or paint, a dent caused by a blow with a hammer) as a possibility for chance to act on. This established fact will then react; it changes according to changes of

light, temperature and air conditions in the studio. Dolven will then, in turn, act upon the changed surface of the painting.

As such, the oil paintings are made of a series of cumulative moments performed in time, which can be reconstructed by the viewers as they walk through the show, exposed to the visual traces of those moments.

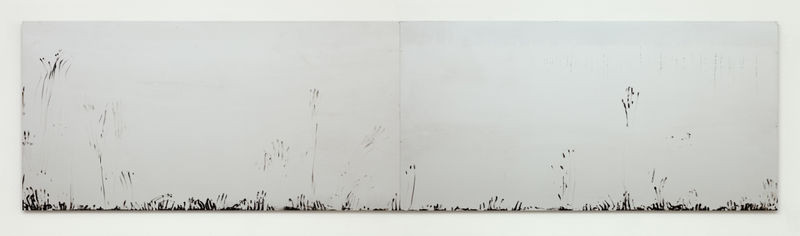

A4 horizon (oil painting for travellers) (2014)

As I have already said, the surface of the rectangles is enlivened by visible traces of the artist’s work; starting from a cold metal sheet, Dolven has applied layers of gesso before different layers of black oil paint are carefully worked onto the metal sheet. The velvet-like tone of the colour interacts with the cold metal, thus evoking warmth. While applying the colours with a pallet knife,

Dolven is using her body pressure to shape the texture of the surface, and this act attributes a strong physical atmosphere to the paintings – both in the creative process and in their reception.

In one 1.25 x 5 format painting the artist’s body itself becomes the pallet knife.

Despite the unobtrusiveness of subject matter, colour and size, the absence of an identifiable motif and the relatively small format of the other floating, matte/multilayered blacks or hazy whites draw the onlooker to the paintings as to a screen. They are environments for the

mind, openly suggestive.

seeing is about thinking (2012)

Individually or together, these works breathe and move, staring back at the onlooking viewer. Their atmosphere is evanescent, and it changes slightly from one day to the next, subtly echoing the mood of that particular day, of its ever changing light, and, of course, of the never

stable state of the viewer’s mind.

These matte planes of shifting darkness are limbo spaces between inner and outer reality, and the new work binds together themes that Dolven has been developing over a long period of time; the formal, material, perceptual and emotional effects of artistic expression bordering on the immaterial, the unseen.

don’t worry I’ll lift the sky (2013)

Throughout her career Dolven has pursued an artistic inquiry into the human condition which she has interlinked with important issues such as the mechanisms of human perception, the subconscious functioning of memory and emotions, thoughts about the passage of time and the importance of historical objects and the human traditions connected with them, the study of the

beauty of the human form as well as the importance of an active understanding of today’s society and politics.

It is always the concept that forms the core of Dolven’s urgent interests – the medium or the techniques vary according to the work of art. Dolven’s concepts often

circle round a precarious moment in time: a moment of change, of struggling for balance, of collective effort or of shaping an evanescent stream of air into something concrete through the human voice.

JA as long as I can (2012)

Dolven’s sound work ‘JA as long as I can’- a collaboration with John Giorno - is an exploration into the quality of sound as a potent signifier of many things at the same time: of corporeal and temporal presence, of emotional as well as informational meaning, of the acute experience

of spatial presence and absence, of harmony or dissent amongst human beings, as well as of the passage of time. Dolven’s new sound piece also invites reflection on the different ways to experience time and to think about time. Different time levels are being explored here alongside a reflection on the psychological processes that structure time; exhaustion and fatigue, impatience, the will of expression, of filling and structuring

the flow of air, of struggling for air.

As an artistic endeavour, ‘JA as long as I can’ is also a study of the human voice as humankind’s oldest instrument and medium. Dolven’s sound piece poignantly shows that the human voice is, at the same time, markedly physical and highly ephemeral. Here sound literally travels in time and space: from Norway to the East coast of the USA, from a female European visual

artist in her fifties to a male, North American spoken word artist in his seventies. Both performers stand for their respective cultural time, and both their voices are consequently tinged by time, by their differing gender, their respective upbringing, by a varying life experience as well as by their emotional proximity or distance to the Norwegian language.

In Dolven’s use of the single affirmative word “ja”, she explores the material qualities of the male and the female vocal cords in motion, and the many different emotional hues these qualities can transmit to the listener. These two unseen bodies physically interact with each other along the rhythms created through the different lengths of breath it takes to utter the word “ja”, resulting in varying expressions.

Dolven explores the fields of darkness, light and the human voice, and she establishes a psycho-aesthetic bond that links these together.

London, January 2014